Vernacular Here&Now

Arbeit an der EiABC, Chair of Architectural Design II mit Antenne Tesfaye | 2013

A theoretical approach to modern Ethiopian architecture that claims the liberation from any imported models and thus enhances innovation in the building sector pushing the evolvement of an independent architectural language.

At the Chair of Architecture and Design II a new architectural creative manifesto was conceived in search of a more suitable architecture for Ethiopian cities. Creative manifestos in general are simple rules or principles also referred to as dogma. Such dogmas were successfully applied in film, theater, literature and dance (1,2,3,4).

In this work we present ten rules, which were formulated following the outcomes of a basic research on the meaning of design in the context of Ethiopia in a time of change.

We found that the design principles of vernacular architecture have the potential to be a suited base for the development of more sustainable architecture for the Ethiopian cities.

Furthermore we present architectural designs on three different scales, ranging from a refurbishment project a new building till the design of an entire building block.

As Ethiopia has culturally never been dominated by colonial powers we are seeking for a bridge between the vernacular past towards an urban future apart from imported models. This approach contains the potential of a proper architectural language of modern Ethiopia.

The Dorze-House (Fig.1) in the cool hills of Chencha with its compactness, inner partition walls and vertical inside space makes use of Bamboo available abundantly and allows the lightning of a small re during the night.

Creative Manifestos in Film, Dance, Theatre and Writing:

In 1995 a group of Danish filmmakers found themselves in a similar situation like architects in Ethiopia today when they sensed the overwhelming effect of an emerging globalized, predominately American film industry. Those Danish filmmakers challenged themselves with a set of ten rules, the so-called “Vow of Chastity – Dogma ‘95” in order to put themselves voluntarily some boundaries to develop their movies – thus they freed themselves from other conventions that come with the Hollywood-industry such as the abundant use of music and visual effects.

Via their rules they forced themselves to avoid such sensational techniques. Instead they focused on real life stories, which played in real life situations and showed highly authentic characters.

The purist dogma-movies became very successful and the rules were adopted by directors from various backgrounds all over the world.

Similar creative dogmas are Yvonne Rainer’s “No to spectacle, No to virtuosity!”, the “Surrealist Manifesto” by André Breton, including the technique of automatic writing and Berthold Brecht’s epic theater. Examples from Architecture are Le Corbusiers five points and the “Laufen Manfesto for a Humaine Design Culture” launched in November 2013. Those rules aimed at the purification of the creative work from certain elements that were perceived as being outdated, alien, crooked or morally vile. (5)

On one hand side rules limit the creator in their work but on the other hand the ideas that they wanted to express could come to a new intensity. The rules allowed the creator to focus on the issues that they found to be most meaningful. In this sense limitations can result in freedom.

In the following we present our reflection about the meaning of design in the context of Ethiopia at this moment of change. This reflection let to the formulation of the “Dogma '13 – Vernacular Here & Now”.

The Tigray-House (Fig.2) with it’s at roof is built from stone masonry. An inner courtyard provides the residents with a comfortable shaded space for handcraft and living.

Innovative approaches to architectural design can significantly contribute to the prosperity of a country; it can address the challenge of climatic change, social health and happiness. Architectural form expresses the identity of a place. Having this in mind we claim that architects have to develop the skills and methods that enrich the country in the broadest sense and contributes the most efficiently to its economic, ecologic and socio-cultural sustainability. The architectural form must not be an objective but be used as a tool to achieve the goals mentioned above.

Vernacular architecture is based on localized needs and construction materials. It tends to evolve over time and to reflect the environmental, cultural, technological, and historical context in which it exists.

A selection of examples from Ethiopia shows the diversity of built forms that have been developed in relation to their environment:

The Gurague-House (Fig.3) with its dome-like roof and its earth flooring is built communally by excellent builders. The wooden roof is put under tension in order to make it long lasting.

Urban varnacular architecture in Nördlingen, Germany (Fig. 4)

In many regions of the world vernacular techniques have been used to built in an urban context. A selection of examples is given in Figure 4 and 5. These contrasting urban styles from very different cultural backgrounds show the potential of architectural identi cation fostered by vernacular techniques.

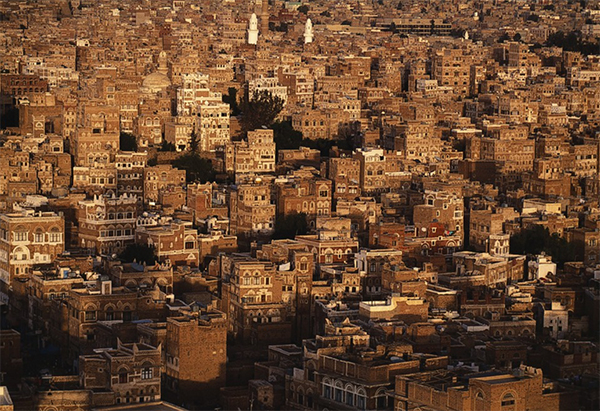

Urban varnacular architecture in Shibam, Yemen (Fig. 5)

Urban varnacular architecture in Kyoto, Japan (Fig. 6)

Urban varnacular architecture in Butzbach, Germany (Fig. 7)

The modernist movement and it’s successor the international style ordinated from a declared rejection of history and to some extent the declared rejection of place. They claimed that a purely rational architectural form is globally the same. Thus local materials, local knowledge, local identity and locale economic and climatic conditions have been denied. (7)

Those problems that result from this ignorance of local conditions have been strongly criticized by the followers of structuralism, a group of international architects highly inspired by vernacular architecture. Today as the climate change has become evident as a result of the industrial era more localized building methods seem to be highly appropriate (8).

Vernacular architecture can be seen as a common understanding of built space with is unconsciously global. It is global because of its natural rationality which it includes.

It seems logical that in times of globalization the natural, synergetic and complex character of the vernacular architecture can show solutions of how to create healthy environments with a strong identifiable character.

In the following we present ten rules that we have generated as abstract principles of the vernacular architecture.

These rules are a tool for the designer. As stated above the designer shall be charged with the responsibility to “develop the skills and methods that enrich the country in the broadest sense and contributes the most efficiently to its economic, ecologic and socio-cultural sustainability. The architectural form must not be an objective but be used as a tool to achieve the goals mentioned above.”

Dogma 2013

Vernacular Here & Now

- Expense and use of imported materials must be minimized.

- Local construction skills have to be applied to a maximum.

- The use of innovative techniques has to be maximized.

- The building must use passive design as much as possible.

- All resource input has to be compensated (unklar), waste that cannot be reused has to be minimized.

- The return (outcome?) of the building must compensate the life cycle cost.

- The number of people that benefit from the architecture has the be maximized, socially, economically, culturally.

- Each building must have a role in forming a neighborhood.

- Common facilities have to be emphasized.

- No imitation of a ‘style’.